In a hectic summer, the rise of the group calling itself the Islamic State (ISIS) has undoubtedly been the biggest story. Unfortunately, much of the media’s analysis comes with misconceptions that need to be addressed. I’ve been researching ISIS for over a year, in large part by following its popular Arabic-language social media accounts and spending time in a handful of Middle Eastern countries. The Islamic State takes itself and its image very seriously, committing and publicizing violent atrocities to establish its legitimacy. The group’s desperation to prove itself as the leader of the Islamic world gives it a resilience simple airstrikes will not be able to subdue.

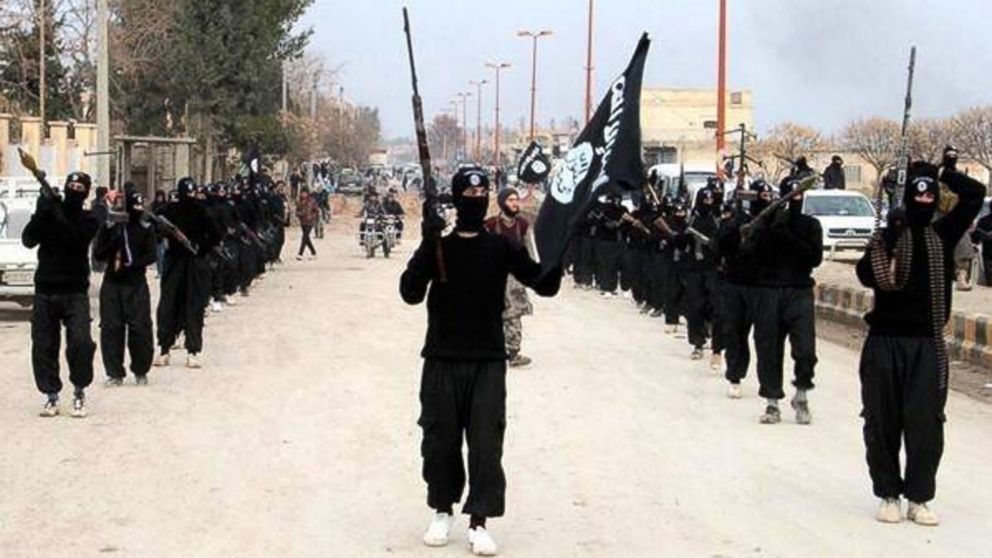

Everyone seems to know that ISIS is an extremist terrorist organization. Yet what truly sets it apart is not its strict interpretation of shari’a and its violence, but instead its conceit. ISIS operates with astonishing self-importance. Most extremist groups believe in waging jihad towards the eventual end of reestablishing the Caliphate (the historical religious and political leadership of Islam), but ISIS takes this goal a step further. It is not fighting to create some future Caliphate: it is the new Caliphate. As such, ISIS takes military expansion and the application of religious law very seriously—it has to prove that it deserves the grandiose title it gives itself. This means conquest and consolidation at the expense of anyone who stands in the way. ISIS web boards are full of documentation of the decapitated heads of ISIS’ enemies.

This arrogance is not new. It has been making many others in the jihadi community angry for a long time. Many news outlets call ISIS an “al-Qaida affiliate.” This characterization is dangerously misleading, but it’s an easy way out of the complexity that surrounds this group’s identity. We often mistakenly think our enemies are united, but for over a year now, al-Qaida has been battling ISIS directly. The predecessor to ISIS was the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI), founded in 2003 in the wake of the U.S.-led invasion. The ISI acted as al-Qaida’s branch in Iraq, but as its name suggests, it intended to be a state, and not just another militant group. Its hostility towards fellow Sunni Muslims garnered heavy criticism, but the ISI justified it, claiming that any Muslims not part of the Islamic State were against it.

When the Syrian crisis began to unfold, the ISI took advantage of the instability and in January 2012 founded a branch in Syria, calling it Jabhat an-Nusra. The group’s extremist views worried moderate rebels, but Jabhat an-Nusra turned out to be a formidable fighting force and was generally willing to cooperate with other rebels. Later, in April 2013, the ISI announced that it was now ISIS and added Syria to its jurisdiction, claiming that European-drawn national boundaries shouldn’t divide those fighting for Islam. Naturally, Jabhat an-Nusra was upset at this takeover by its founder. In the ensuing battles, al-Qaida Central backed Jabhat an-Nusra, disowning ISIS officially in February 2014. The struggle continues, but ISIS has the upper hand, enjoying a stable (if subjugated) foundation in Syria and now stunning military success in Iraq.

Such internecine violence is not simply a turf war but originates in two opposed conceptions of the methods and purpose of jihad. The supporters of al-Qaida embrace a relatively patient strategy, one that includes cooperating with groups with different beliefs but similar short-term goals—the enemy of their enemy can be their friend. ISIS does not compromise or cooperate; everyone is an enemy. And thus we end up with the absurdity of al-Qaida seeming moderate by comparison.

This bloodthirsty enemy seems to deserve U.S. military action, but our limited airstrikes can’t do much more than defend our Kurdish allies and certain regional minorities. These are noble goals, but we shouldn’t pretend that they will stop ISIS or solve the larger humanitarian crisis that still mostly originates in Syria’s chronic instability. Our goals need to be defined. ISIS has threatened the U.S., but thus far it has focused on a “near-enemy” strategy, aiming first to build its state. Our concern need not be our own national security—not yet, at least. Our concern should be helping regional powers restore order where we helped to drive it out. ISIS has made enemies of everyone, which means there is an opportunity for us to make friends. For once, the Middle East is united about something. Whether its states can work together remains to be seen, but the fact remains that the US should not be going at it alone. We can aid those we trust (the Kurds, for example), engineer cooperation, and otherwise focus our efforts on the refugees displaced by the chaos. This is a time for diplomacy as much as for military action.